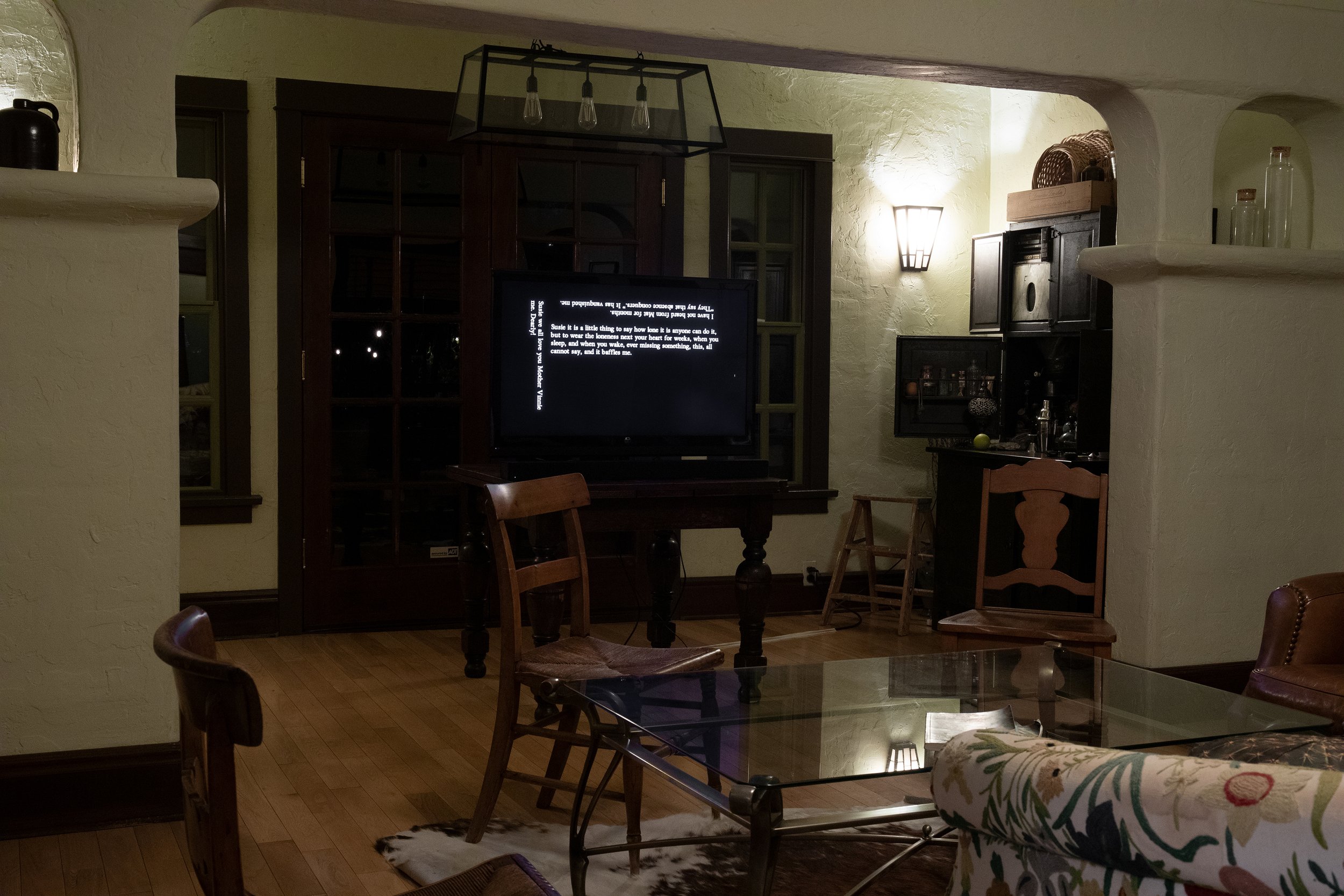

Oh Matchless Earth

Oh Matchless Earth was a site-responsive installation at The Residency Project in Pasadena, CA in December 2021. Appropriate the residency’s early 20th Century craftsman style house, the installation explored issues of interiority in the COVID-19 Era, intentionally retaining the domestic aspects of the space. The project started with year-long reading of Emily Dickinson’s letters to her sister-in-law Susan Huntington Dickinson and expanded to other topics of reading as a pandemic-era practice. Involving video, painting, and sound, the installation was organized into three thematic rooms with the accompanying texts below.

I

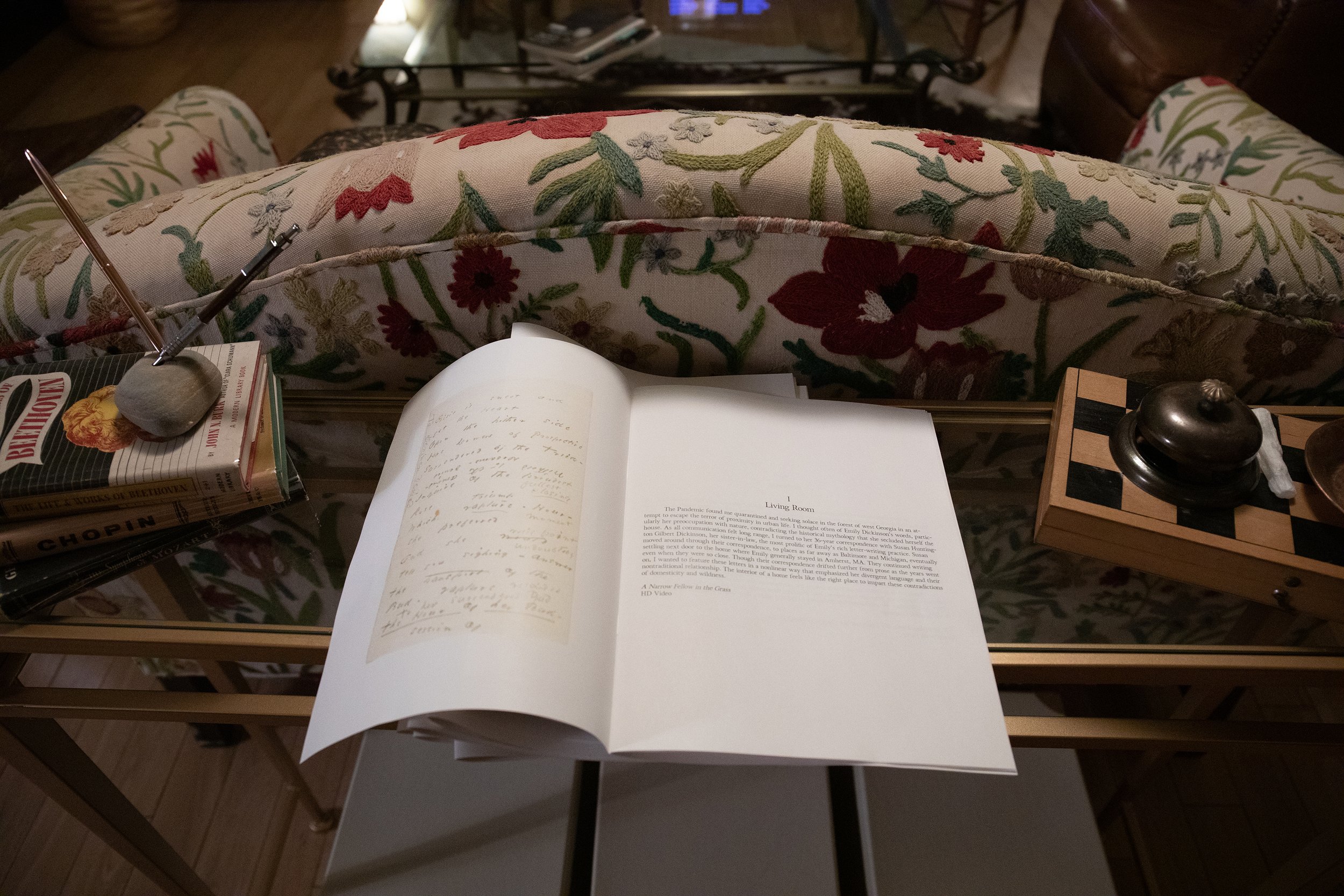

Living Room

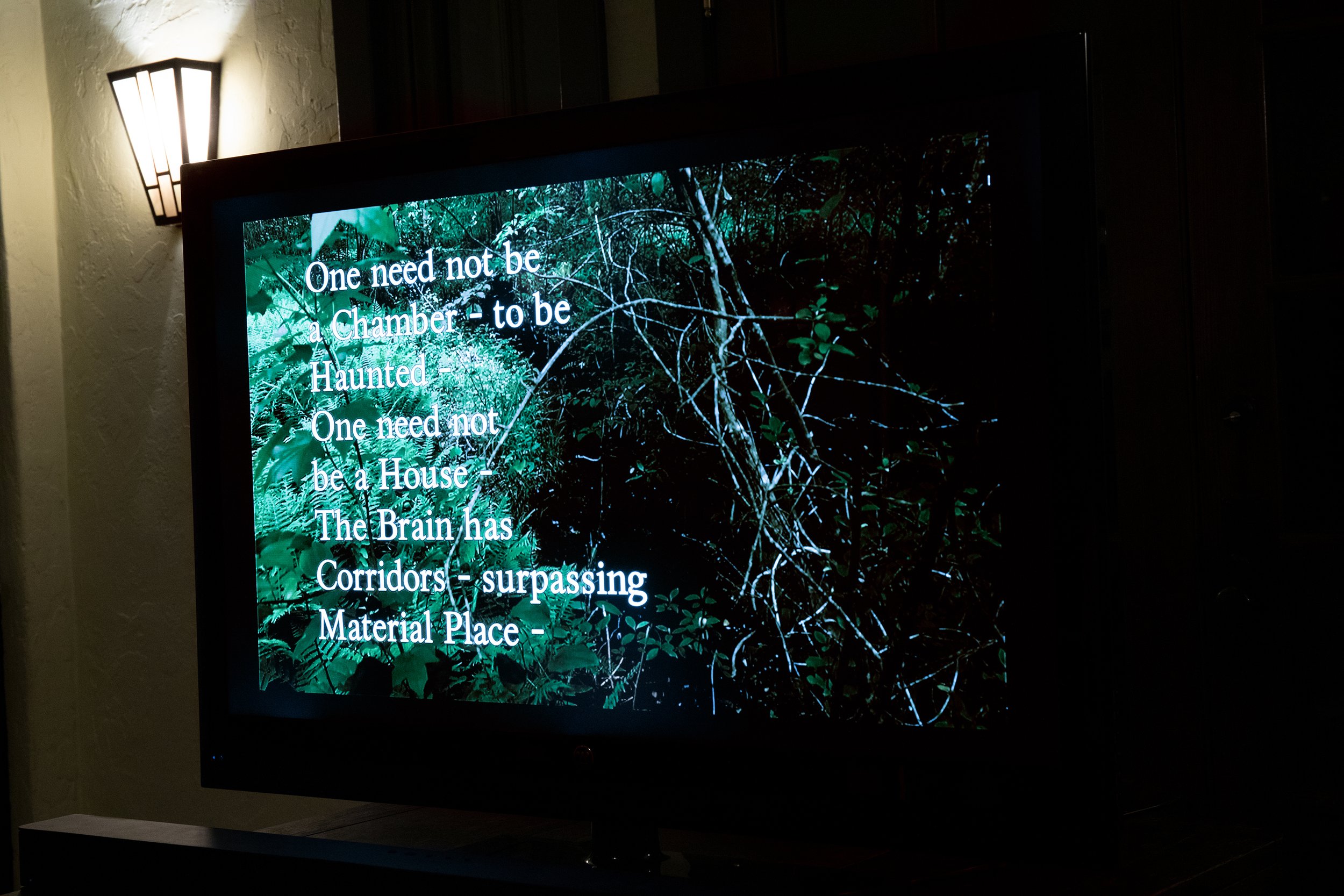

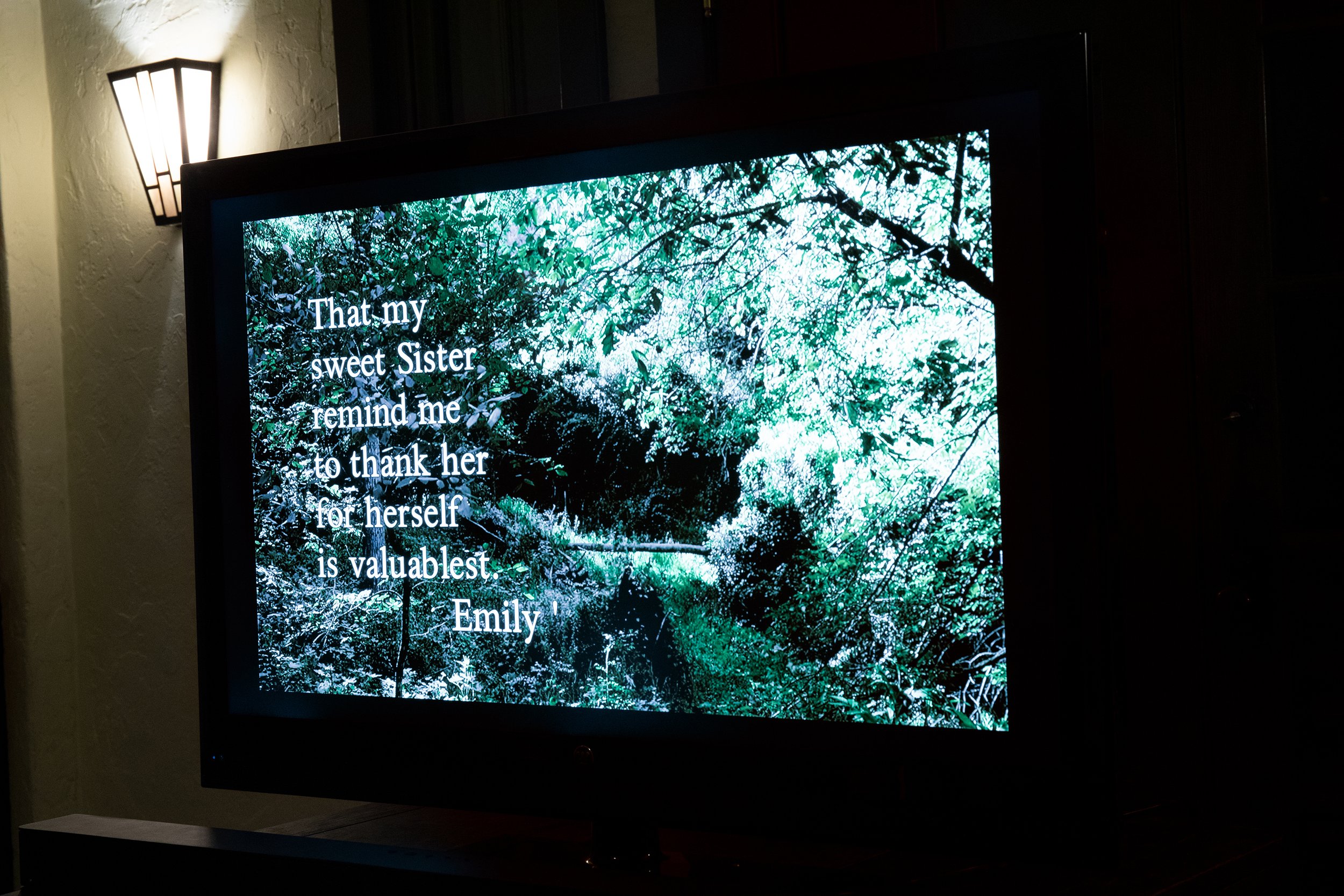

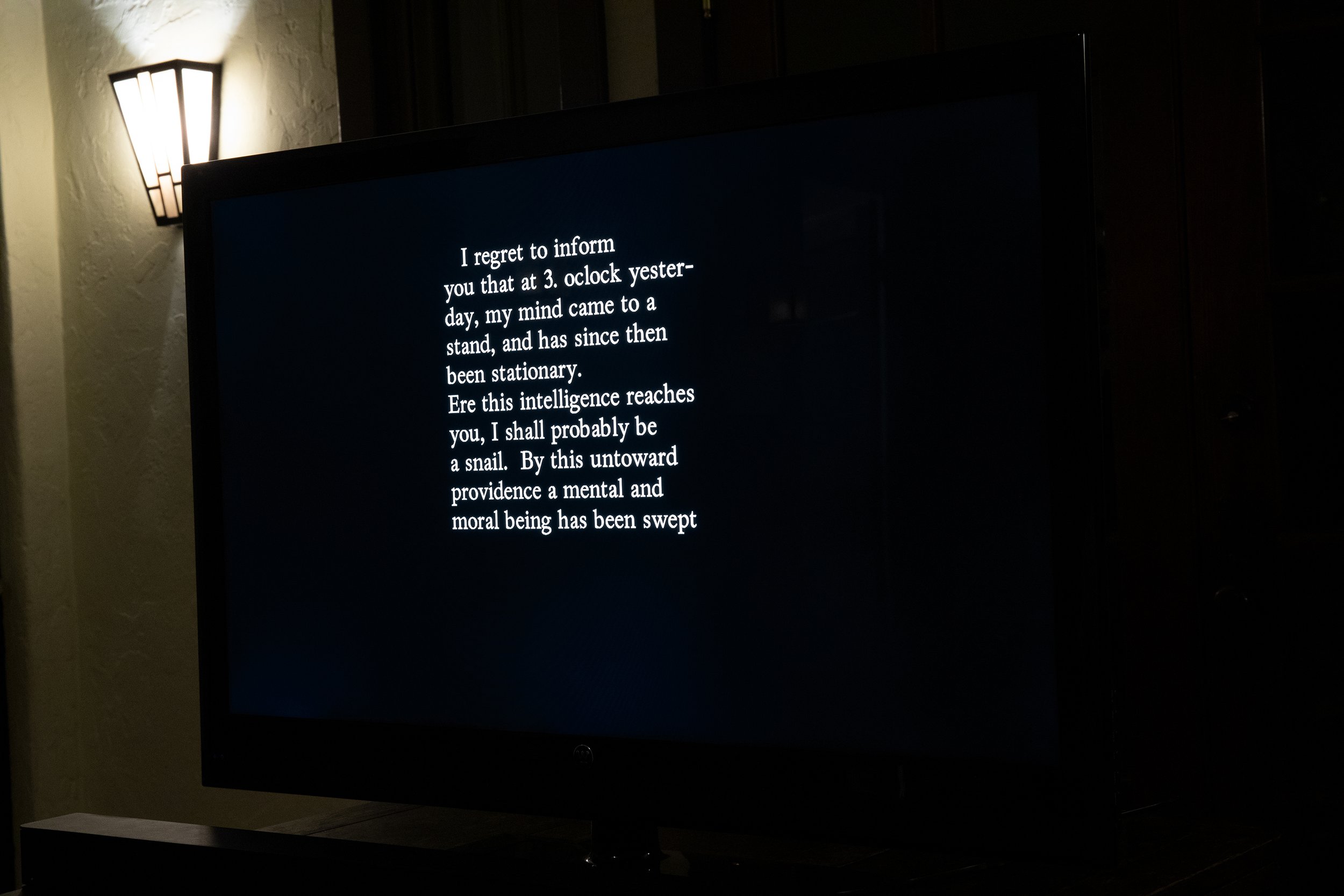

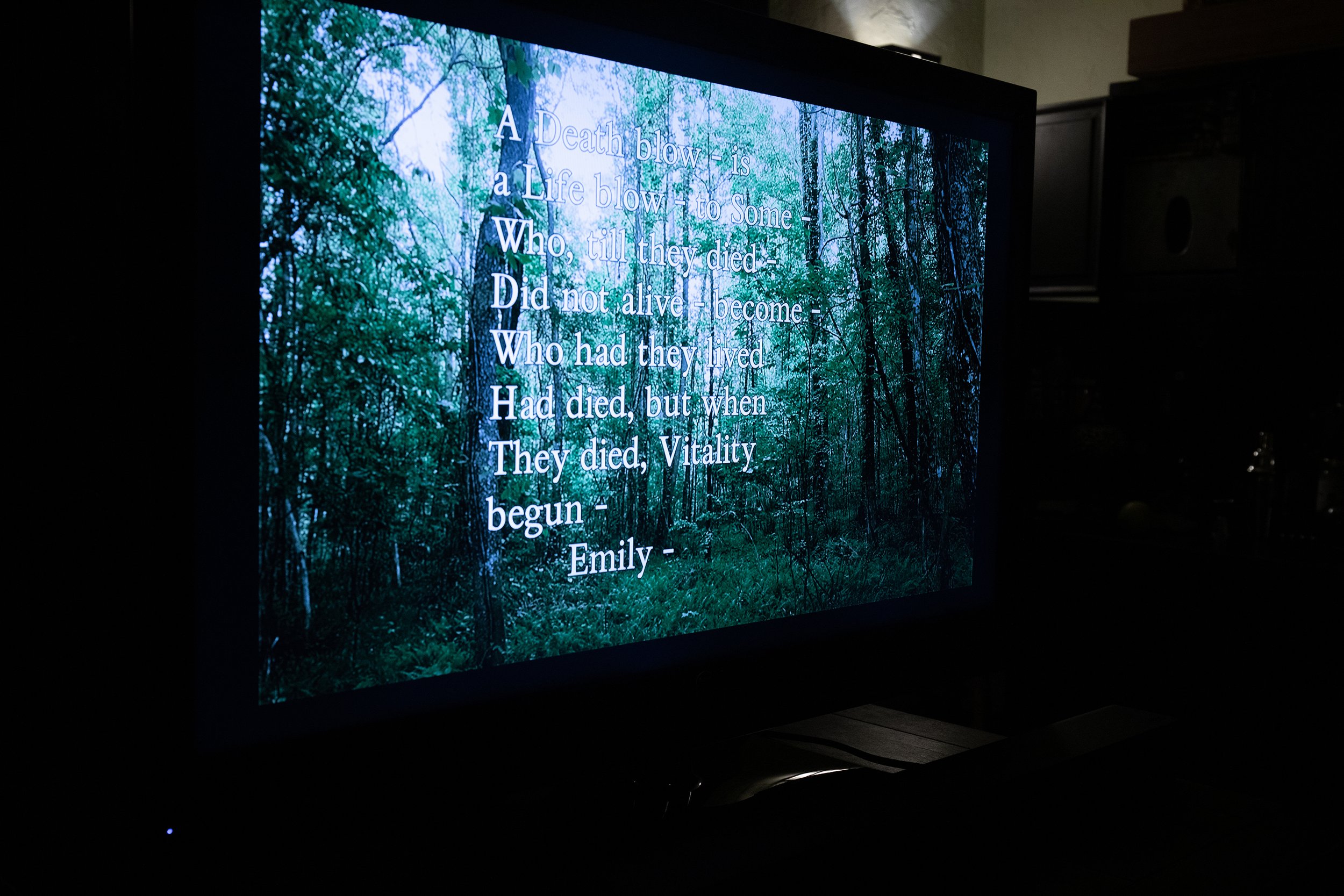

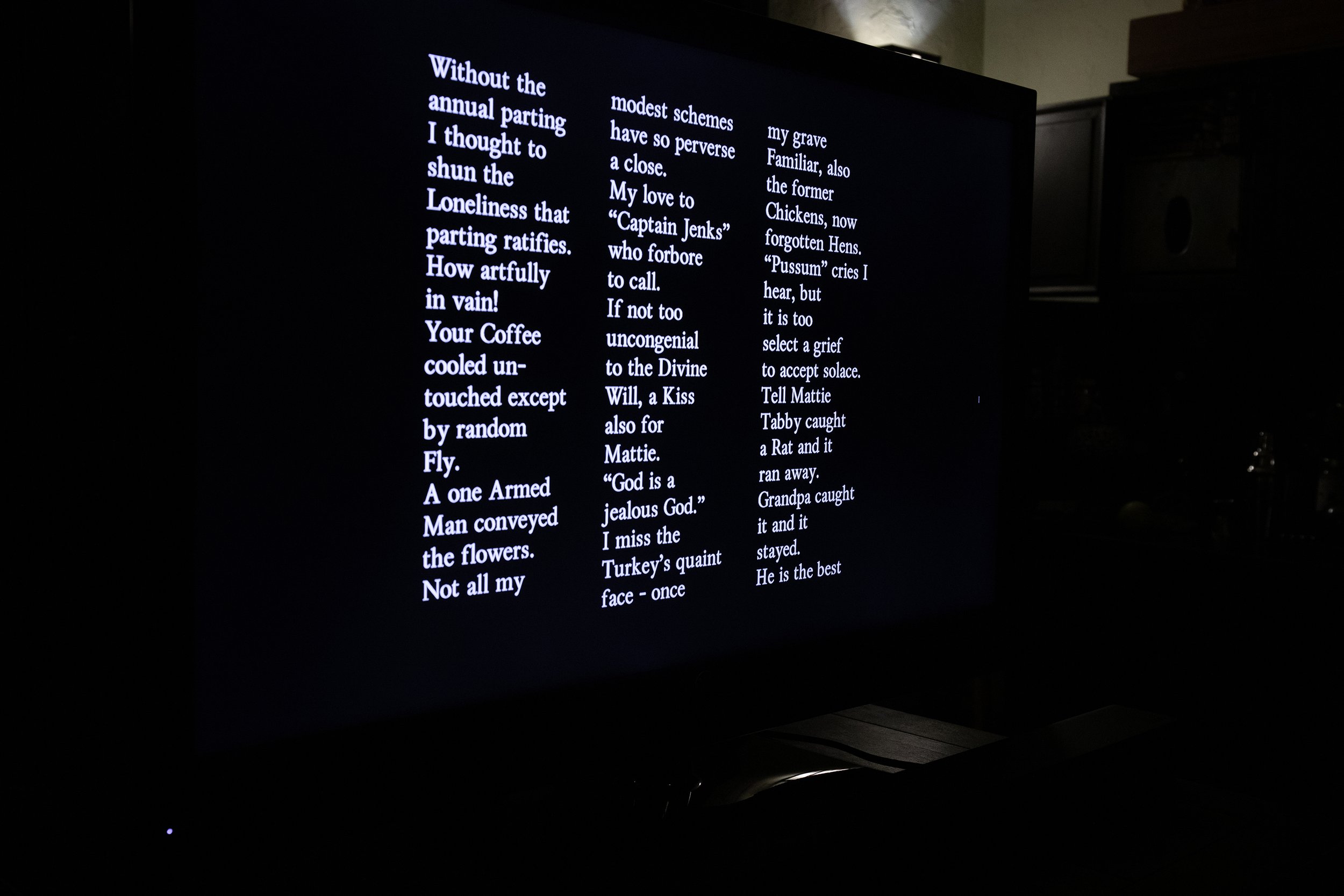

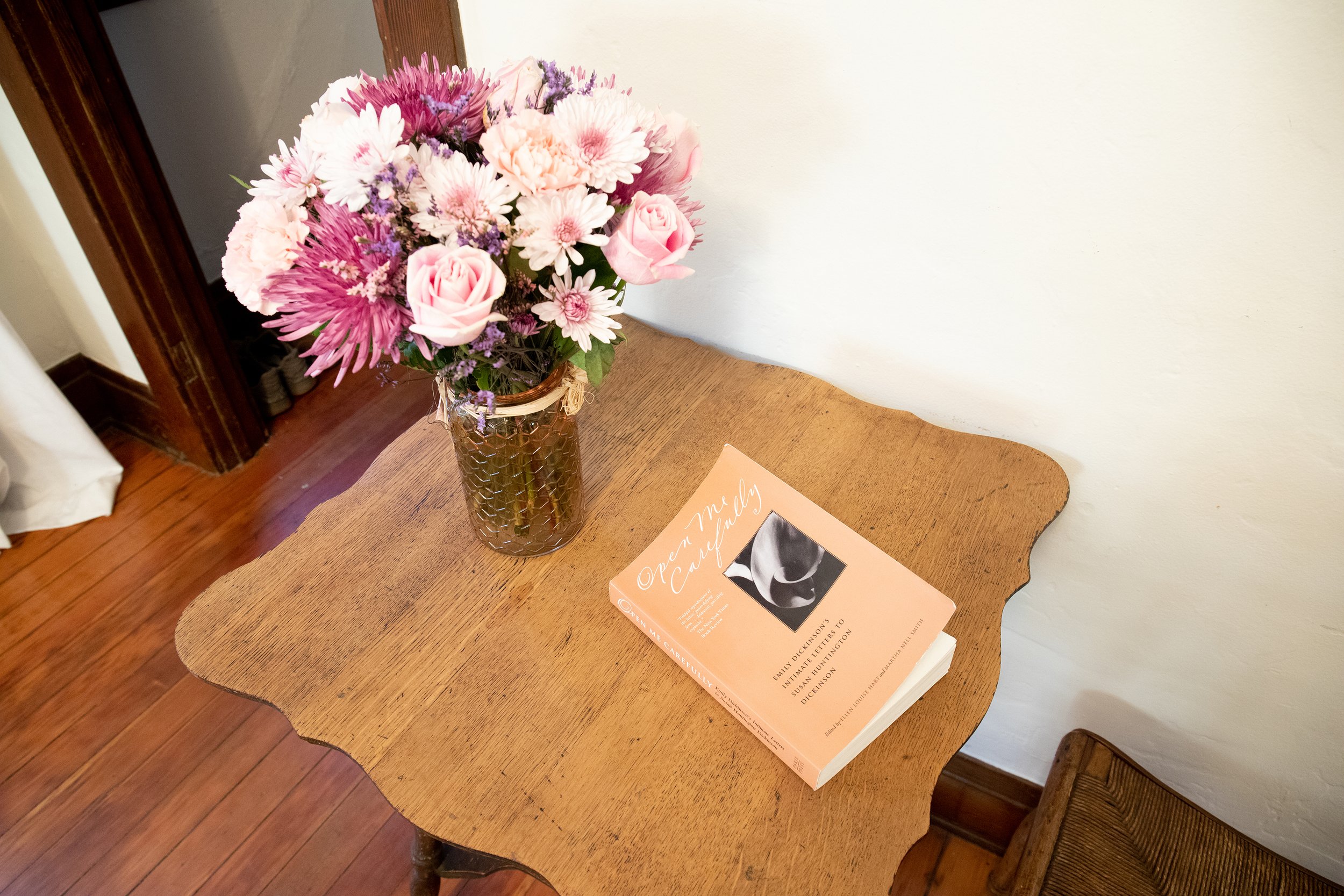

The Pandemic found me quarantined and seeking solace in the forest of west Georgia in an attempt to escape the terror of proximity in urban life. I thought often of Emily Dickinson’s words, particularly her preoccupation with nature, contradicting the historical mythology that she secluded herself the house. As all communication felt long range, I turned to her 36-year correspondence with Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson, her sister-in-law, the most prolific of Emily’s rich letter-writing practice. Susan moved around through their correspondence, to places as far away as Baltimore and Michigan, eventually settling next door to the home where Emily generally stayed in Amherst, MA. They continued writing even when they were so close. Though their correspondence drifted further from prose as the years went on, I wanted to feature these letters in a nonlinear way that emphasized her divergent language and their nontraditional relationship. The interior of a home feels like the right place to impart these contradictions of domesticity and wildness.

A Narrow Fellow in the Grass, HD Video, 10-minute excerpt, total running rime: 1:25:00, contact for full version

II

Bedroom

i

In their compilation of correspondence between Emily and her sister-in-law, Ellen Louise Hart and Martha Nell Smith speculate that two cultural factors may have caused their correspondence to be largely overlooked for most of a century. “The first is the stereotypical nineteenth-century vision of the ‘Poetess’ as a tortured, delicate woman dressed in virginal white, pining way in seculsion, removed from the vibrant nit, grit, and passion of normal life.” The narrative that Emily was a recluse was pushed by Mabel Loomis Todd, one of her first editors, and the mistress of Austin Dickinson, Emily’s brother and Susan’s husband. While Todd constructed this narrative, she also meticulously erased – sometimes literally – any mention of Susan. For me, the consistent, florid, and specific references to nature have always complicated this mythological image of Emily Dickinson sitting alone in her bedroom. Despite common, ableist assumptions concerning Dickinson’s deviations from normative life, she seems to me to represent different but simultaneous paradigms of isolation relevant to shelter-in-place. The mysteriousness of her coded word choices gives a feeling that the writing surrounds one like an atmosphere or wilderness.

Perhaps it is unfair to count Emily among the pantheon of neuro-divergent thinkers who have radically changed our language and culture, but disability theory tells us to find the abilizing features of difference. Whether we understand her deviations in life and words, they were a beautiful turning point in the English Language.

Oh Matchless Earth, We Underrate the Chance to Dwell in Thee, gouache on paper, 72 x 60”

ii

The other cultural factor that Hart and Nell consider is that according to a nineteenth-century view on intimate female friendships, “women of Dickinson’s time often indulged in highly romantic relationships with each other, but these relationships were merely affectionate and patently not sexual. Such same-sex attractions, so the popular wisodm goes, had the character of an adolescent crush rather than a mature erotic love.” In their collection, they do, at times, push the narrative that the relationship between Emily and Susan was mature and erotic despite Susan marrying her brother Austin. To me, it has never felt productive to speculate on these details, because to do so seems to miss the point that their relationship was rather undefinable, which is the more queer, compelling, and self-evident narrative.

We Meet no Stranger but Ourself, gouache on paper, 72 x 60”

III

Attic

i

The poet and Americanist literary scholar Susan Howe is a major instigator of my interest in Emily Dickinson as well as my interest in mining and iterating textual histories. In her book The Midnight, she illustrates and describes “some anonymous American preschooler’s” scrawled stick figure in the inside cover of an Irish song book. “More diagram than imp” she calls it. I remind myself of the overcome unlikelihood of my hand retracing Emily’s motions in her thoughtful but brief impulse to send a coded note to her sister-in-law. Thinking too of her use of marginalia, I think of this drawing in the margin and its iteration from pen to halftone dot to my reinterpretation.

Marginalia I, gouache on paper, 72 x 60”

ii

My copy of The Midnight was previously owned and is full of idiosyncratic circled words and torn sticky tabs. In the inside cover is a list ostensibly of vocabulary words whose free associative connection to one another or the text is subject to pure speculation. The implied presence of a stranger’s hand is oddly comforting. Retracing it feels like a brush with impossibility.

Marginalia I, gouache on paper, 72 x 60”

iii

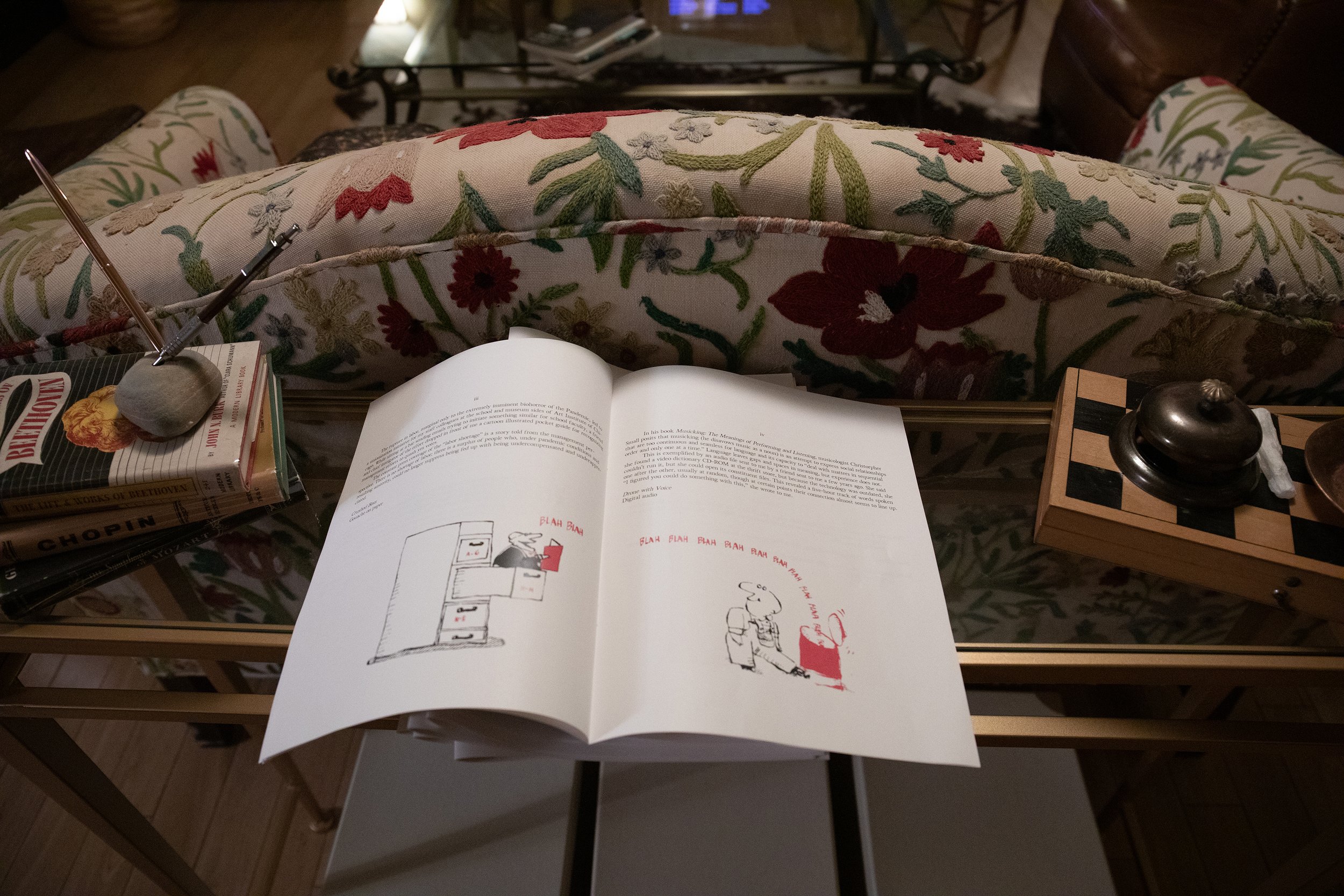

The rupture in labor, marginal only to the extremely imminent biohorror of the Pandemic, led to a unionization initiative for my staff colleagues at the school and museum sides of Art Institute of Chicago. While sitting at a bar sending emails trying to initiate something similar for school faculty, a friend and chief instigator of the effort dropped in front of me a cartoon illustrated pocket guide for recognizing management efforts to quash yes votes.

The constant press coverage of the “labor shortage” is a story told from the management perspective. There is no shortage of labor; there is a surplus of people who, under pandemic conditions and resulting austerity, could no longer suppress being fed up with being undercompensated and underappreciated.

Crushed Boss, gouache on paper, 60 x 72”

iv

In his book Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening, musicologist Christorpher Small posits that musicking (he disavows music as a noun) is an attempt to express social relationships that are too continuous and seamless for language and its capacity to “deal with matters in sequential order and only one at a time.” Language leaves gaps and spaces in meaning, but experience does not.

This is exemplified by an audio file sent to me by a friend sent to me a few years ago. She said she found a video dictionary CD-ROM at the thrift store, but because the technology was outdated, she couldn’t run it, but she could open its constituent files. This revealed a five-hour track of words spoken one after the other, usually at random, though at certain points their connection almost seems to line up. “I figured you could do something with this,” she wrote to me.